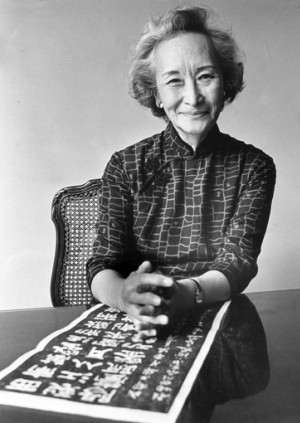

Nien Cheng 鄭念

© IsaacMao. Licensed with CC BY 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Biography

Nien Cheng was born in Beijing, China, in January 1915 and studied at Yenching University and then obtained a Master’s degree at the London School of Economics and Political Science, where she met her future husband, Dr Kang-chi Cheng.

In April 1949, she returned to Shanghai, China with her husband who was transferred from the Chinese Embassy in Australia to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the nationalist government. One month later, the Communist army occupied Shanghai and Dr Cheng remained to join the foreign service for the new government. In 1950 he became the general manager of Shell Oil in Shanghai, which was one of the few foreign corporations allowed to operate in China after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. After Dr Cheng died in 1957, Mrs Cheng was invited to join the company as an advisor.

1966 saw the launch of the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” and in August that year, Nien Cheng was placed under house arrest accused of spying for the UK after the Red Guards ransacked her house and confiscated her property. In September she was imprisoned in Shanghai’s First Detention Centre.

During her six-and-a-half-year incarceration, Nien Cheng was subjected to interrogation, torture and solitary confinement but she refused to confess to the crimes she was accused of committing. In 1973, when she was released from prison, she was told that her daughter Meiping, a prominent Shanghai film actress, had committed suicide in 1967. She later discovered she had been murdered by the Red Guards.

In October 1978 government officials apologised for Nien Cheng’s wrongful arrest and imprisonment, and in 1980 she left China for Canada before settling in America. Her memoirs, Life and Death in Shanghai were published in 1987 and became a best-seller. She died on 2 November 2009, aged 93.

Writing sample

Within the gloomy cell, I studied Mao’s books many hours a day, reading until my eyesight became blurred.

One day, in the early afternoon, when my eyes were too tired to distinguish the printed words, I lifted them from the book to gaze at the window. A small spider crawled into view, climbing up one of the rust-eroded bars. The little creature was no bigger than a good-sized pea; I would not have seen it if the wooden frame nailed to the wall outside to cover the lower half of the window hadn’t been painted black. I watched it crawl slowly but steadily to the top of the iron bar, quite a long walk for such a tiny thing, I thought. When it reached the top, suddenly it swung out and descended on a thin silken thread spun from one end of its body. With a leap and swing, it secured the end of the thread to another bar. The spider then crawled back along the silken thread to where it had started and swung out in another direction on a similar thread. I watched the tiny creature at work with increasing fascination. It seemed to know exactly what to do and where to take the next thread. There was no hesitation, no mistake, and no haste. It knew its job and was carrying it out with confidence. When the frame was made, the spider proceeded to weave a web that was intricately beautiful and absolutely perfect, with all the strands of thread evenly spaced. When the web was completed, the spider went to its centre and settled there.

I had just watched an architectural feat by an extremely skilled artist, and my mind was full of questions. Who had taught the spider to make a web? Could it really have acquired the skill through evolution or did God create the spider and endow it with the ability to make a web so that it could catch food and perpetuate its species? How big was the brain of such a tiny creature? Did it act simply by instinct, or had it somehow learned to store the knowledge of web-making? Perhaps one day I would ask an entomologist. For the moment, I knew I had just witnessed something that was extraordinarily beautiful and uplifting…

From ‘The Spider’ in This Prison Where I Live, ed. Siobhan Dowd (London: Cassell, 1996). ISBN: 0-304-33306-9

Useful links

Wikipedia on Nien Cheng: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nien_Cheng

Nien Cheng’s obituary, 2009: http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2009/nov/10/nien-cheng-obituary

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/politics-obituaries/6545847/Nien-Cheng.html