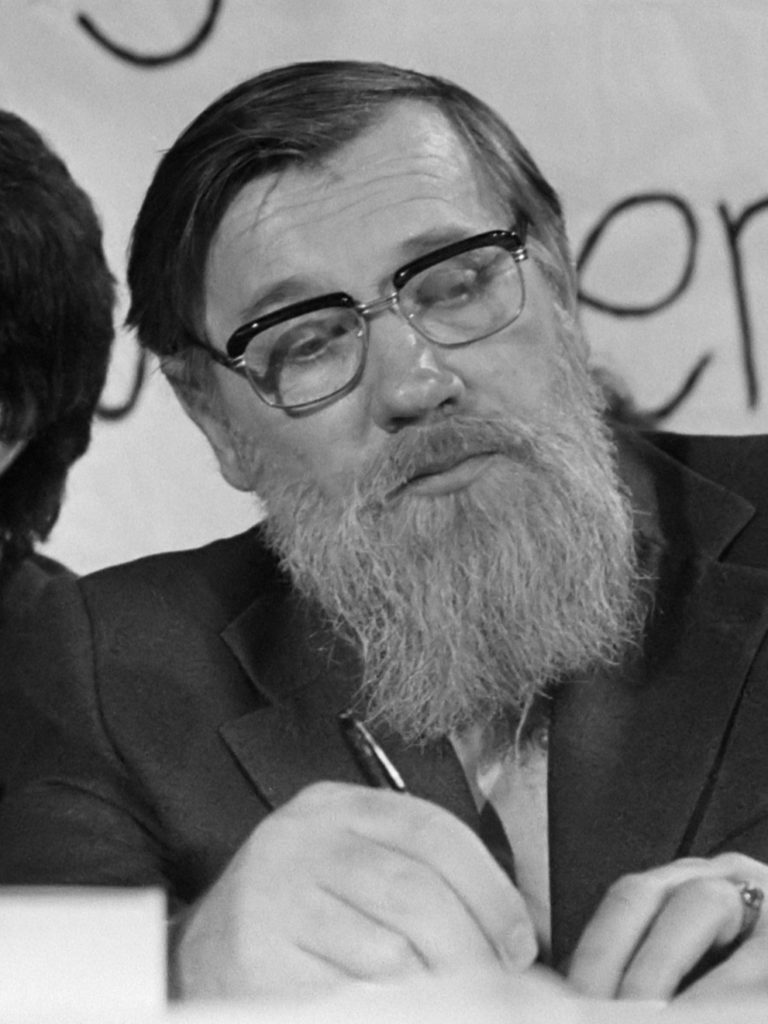

Andrei Sinyavsky in 1975

© Rob Mieremet / Anefo, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Biography

Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel were jointly tried in 1966 for having published satirical articles under pseudonyms abroad. Credited with being the founders of samizdat, (underground publications), they spent years in prison. The trial was said to be symbolic of the end of the ‘Khrushchev thaw’ and the beginning of the Brezhnev era.

Andrei Sinyavsky was born in Moscow in 1925. His father was a Communist party official who was executed in 1951 in the Stalinist purges. In 1949 Sinyavsky graduated from Moscow University and went on to work at the Gorky Institute of World Literature. During the ‘Khrushchev thaw’ he wrote and published numerous articles and short stories about Stalinist Russia including The Fantastic World of Abram Tertz and The Trial is On which were both published in France under the pseudonym Abram Tertz. Sinyavsky was arrested on 8 September 1965. In a show trial the following year Sinyavksy and his friend Yuli Daniel were convicted of ‘anti-Soviet activity’ and the former sentenced to seven years hard labour. Despite his incarceration Sinyavksy continued to write and his letters to his wife were published in the book A Voice from the Choir in 1973. He was released on 8 June 1971 and in 1973 he immigrated to France where he founded a literary magazine Sintaksis. He died in Paris on 25 February 1997.

Writing sample

Andrei Sinyavksy (The Makepeace experiment By Abram Tertz)

Suddenly there was a hold up. Instead of marching past, the crowd jostled in front of the tribune, looking up with curiosity at Comrade Tishenko: he had raised his hand and opened his mouth as if about to speak but his face was working in perturbation and not a sound was coming from his lips, though even the loudspeaker had encouragingly lowered its voice.

…

‘Dear fellow citizens!’ He stopped in obvious agitation. ‘Dear fellow citizens … I wish … We wish … to announce … that this day …’

He twitched, flushed crimson, and the next words came in a rush, all on one note and in a loud expressionless voice.

‘This day marks the start of a new era in the history of Lyubimov. I and the rest of the leadership are voluntarily, I repeat voluntarily, divesting ourselves of our functions, and I now urge you unanimously to elect a leader to replace us … a man who … our pride … our joy … I command … I beg …’

He faltered, gasped and, grabbing his neck with his two hands, squeezed his windpipe as if trying to stop the torrent of words. His eyes bulged, his body swayed to and fro, the boards creaking beneath its weight, and it looked as if at any moment he would fall down dead, strangled by his own hands, when a power evidently stronger than his own loosened the deadly grip, freeing the bruised throat, and his arms, still bent at the elbows and looking like a crab’s claws, were slowly forced back. Standing in this defenceless posture, he concluded:

‘To elect as our supreme ruler, judge and commander in chief,’ – his breath gasped and whistled – ‘Comrade Leonard Makepeace, Hurrah!’

…

Within half a minute, however, isolated voices rang out in the crowd and very soon the whole multitude was stirring, rumbling and shouting its approval of the proposed resolution:

‘Long live Makepeace! Long live our glorious Leonard!’

Only one village lout asked who Leonard Makepeace was and how he had deserved the highest of honours, but he was immediately shouted down:

‘Don’t you know our Lenny Makepeace? Our best mechanic and expert on bycicles! Disgraceful! Back to your village, you ignorant oaf!’

From The Makepeace Experiment trans. Maya Harari ( Evanston :Northwestern University Press, 1989) ISBN-10: 0810108380, ISBN-13: 978-0810108387

Biography

Yuli Daniel was born on November 15 1925 and fought on the Eastern front in WWII where he was seriously wounded. In 1956 he graduated from Moscow Pedagogical State University and went on to become a teacher and member of the Gorky Institute of World Literature. He began to write satirical novels about life in Soviet Russia and like Sinyavsky had them published in Paris under a pseudonym (Nikolai Arzhak). His collection This is Moscow Speaking and Other Stories was also published in America in 1969.

Daniel was convicted o five years hard labour.

After reforms instigated by Mikhail Gorbachev in the late 1980s Daniels’ was semi-rehabilitated and had some of his poems published in Russia. He died on December 30 1989 after suffering a stroke.

Writing sample

Yuli Daniel (Nikolai Arzhak) This is Moscow Speaking

I’ve started painting again. I’m doing particularly good headlines and captions. I use water colours. I’ve got lots of paints and crayons because they all like my painting and everybody gives me them. On my birthday I got a box of coloured pencils. Ivan Alexandrovich gave me them. He was very busy that day but he still came in to wish me a happy birthday.

We’ve got a television set. Not long ago we watched a film in two parts called “The Russian Miracle.” One of the people watching laughed so much he had to be given valerian.

I feel quite well now. It’s just my headaches. And I want to sleep all the time,

Irina came to see me recently. She brought me flowers. She was very sad and cried all the time. Then Ivan Alexandrovich came along and comforted her. He’s very good at it. He told me afterwards that Irina was beautiful.

It’s autumn now and it’s cold already, but they keep the place nice and warm, so I’m not cold. Everyday if it’s not raining I go out for a walk. The garden is wonderful – but a bit too bright, with a lot of yellow and red and it makes my head ache.

Today is the 28th of November, 1963. My name is Victor Volsky.

I found something. I fastened it to the inside of my pants. There are tapes on my pants and I tied the thing to them.

Sometimes, if my head isn’t aching and it’s not raining outside, I feel I want to go somewhere far, far away where there aren’t so many people. They’re all very clever here and very kind, but I’m tired, so tired of having them with me the whole time. I would so much like to be alone.

Now, after my find, I will be able to do just that. But I’m not going to hurry. I’ll wait till it’s winter, till the snow is falling – or even better – till there’s a blizzard so they won’t be able to follow my footprints. I’ll wait for a blizzard in the night, then I’ll put on my dressing gown and open the door with the triangular key I found and hid in my pants. By the way, this key looks just like the ones they use to open railway carriages.

I’ll go away and be alone again.

From ‘Atonement’ in This is Moscow Speaking and other stories, translations by Stuart Hood, Harold Shukman and John Richardson (London: Collier Books, 1968)

Useful Links

Wikipedia entry on Yuli Daniel: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuli_Daniel

Wikipedia entry on Andrei Sinyavsky: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sinyavsky-Daniel_trial

Andrei Sinyavsky obituary: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-andrei-sinyavsky-1280852.html

Yuli Daniel Obituary: https://www.nytimes.com/1989/01/03/world/proudly-a-soviet-dissident-is-buried.html?pagewanted=1